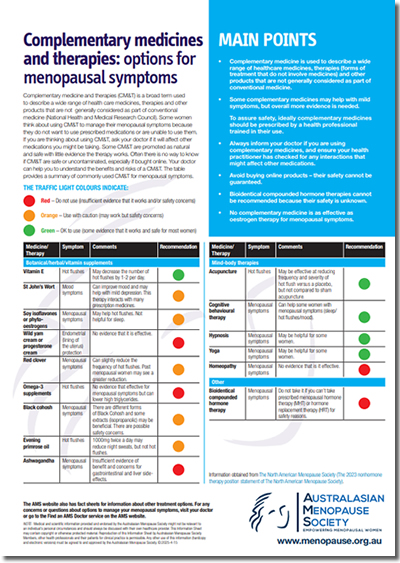

Complementary medicines and therapies: options for menopausal symptoms

MAIN POINTS

-

Complementary medicine is used to describe a wide range of healthcare medicines, therapies (forms of treatment that do not involve medicines) and other products that are not generally considered as part of conventional medicine.

-

Some complementary medicines may help with mild symptoms, but overall more evidence is needed.

-

To assure safety, ideally complementary medicines should be prescribed by a health professional trained in their use.

-

Always inform your doctor if you are using complementary medicines, and ensure your health practitioner has checked for any interactions that might affect other medications.

-

Avoid buying online products – their safety cannot be guaranteed.

-

Bioidentical compounded hormone therapies cannot be recommended because their safety is unknown.

-

No complementary medicine is as effective as oestrogen therapy for menopausal symptoms.

Download:

![]() AMS Complementary Therapies Fact Sheet87.77 KB

AMS Complementary Therapies Fact Sheet87.77 KB

Complementary medicine and therapies (CM&T) is a broad term used to describe a wide range of health care medicines, therapies and other products that are not generally considered as part of conventional medicine (National Health and Medical Research Council). Some women think about using CM&T to manage their menopausal symptoms because they do not want to use prescribed medications or are unable to use them. If you are thinking about using CM&T, ask your doctor if it will affect other medications you might be taking. Some CM&T are promoted as natural and safe with little evidence the therapy works. Often there is no way to know if CM&T are safe or uncontaminated, especially if bought online. Your doctor can help you to understand the benefits and risks of a CM&T. The table provides a summary of commonly used CM&T for menopausal symptoms.

The traffic light colours indicate:

![]() Red - Do not use (insufficient evidence that it works and/or safety concerns)

Red - Do not use (insufficient evidence that it works and/or safety concerns)

![]() Orange - Use with caution (may work but safety concerns)

Orange - Use with caution (may work but safety concerns)

![]() Green - OK to use (some evidence that it works and safe for most women)

Green - OK to use (some evidence that it works and safe for most women)

|

Medicine/Therapy |

Symptom |

Comments |

|

|

Botanical/herbal/Vitamin supplements |

|||

|

Vitamin E |

Hot flushes |

Vitamin E can decrease the number of hot flushes by 1-2 per day. |

|

|

St John’s Wort |

Mood symptoms |

Can improve mood and may help with mild depression. This therapy interacts with many prescription medicines. |

|

|

Soy isoflavones or phyto-oestrogens |

Menopausal symptoms |

May help hot flushes. Not helpful for sleep. |

|

|

Wild yam cream or progesterone cream |

Endometrial (lining of the uterus) protection |

No evidence that it is effective. |

|

|

Red clover |

Menopausal symptoms |

Can slightly reduce the frequency of hot flushes. Post menopausal women may see a greater reduction. |

|

|

Omega-3 supplements |

Hot flushes |

No evidence that effective for menopausal symptoms but can lower high triglycerides. |

|

|

Black cohosh |

Menopausal symptoms |

There are different forms of Black Cohosh and some extracts (isopropanolic) may be beneficial. There are possible safety concerns. |

|

|

Evening primrose oil |

Hot flushes |

No evidence that it is effective. |

|

| Ashwagandha |

Menopausal symptoms |

Insufficient evidence of benefit and concerns for gastrointestinal and liver side effects. | |

|

Mind-body therapies |

|||

|

Acupuncture |

Hot flushes |

May be effective at reducing frequency and severity of hot flush versus a placebo, but not compared to sham acupuncture. |

|

|

Cognitive behavioural therapy |

Menopausal symptoms |

Can help some women with menopausal symptoms (sleep/ hot flushes/mood). |

|

|

Hypnosis |

Menopausal symptoms |

Hypnosis might be helpful for some women. |

|

|

Yoga |

Menopausal symptoms |

Yoga might be helpful for some women. |

|

|

Homeopathy |

Menopausal symptoms |

No evidence that is it effective. |

|

|

Other |

|||

|

Bioidentical compounded hormone therapy |

Menopausal symptoms |

Do not take it if you can’t take prescribed menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for safety reasons. |

|

Information obtained from The North American Menopause Society (The 2023 nonhormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society).

The AMS website also has fact sheets for information about other treatment options. For any concerns or questions about options to manage your menopausal symptoms, visit your doctor or go to the Find an AMS Member service on the AMS website.

Note: Medical and scientific information provided and endorsed by the Australasian Menopause Society might not be relevant to an individual’s personal circumstances and should always be discussed with their own healthcare provider. This Information Sheet may contain copyright or otherwise protected material. Reproduction of this Information Sheet by Australasian Menopause Society Members, other health professionals and their patients for clinical practice is permissible. Any other use of this information (hardcopy and electronic versions) must be agreed to and approved by the Australasian Menopause Society.

Content updated 15 April 2025

MAIN POINTS

MAIN POINTS

The following strategies may or may not work for you. Perhaps choose one suggestion that you aren’t currently doing and stick with it for several weeks.

The following strategies may or may not work for you. Perhaps choose one suggestion that you aren’t currently doing and stick with it for several weeks.

MAIN POINTS

MAIN POINTS MAIN POINTS

MAIN POINTS MAIN POINTS

MAIN POINTS MAIN POINTS

MAIN POINTS